Edition 1

May, 2016.

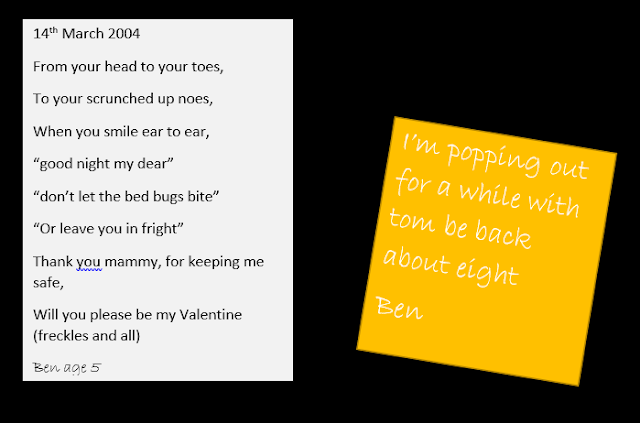

Taking part in this debut OHSC were Alíona Hamilton [aged 13] and Andy Hamilton. The prompt word chosen was Freckles. We chose the topic an hour before the challenge started, to give us a little time to think, then we had 45 minutes of writing time and 15 minutes of tidying up. Alíion's story is told through a series of letters - Andy's is a straight up story. Hope you enjoy.

Freckles

By Alíona Hamilton

---

FrecklesBy Andy Hamilton

Tim was sure we’d find

treasure. He’d been on the lake seven times already that summer, and four times

all the way up to Holy Island, and each time he’d come back with something. Or

so he said.

I tried to look busy as he loaded the rowboat on the pier

in Killaloe. I tangled and untangled the rope from its mooring, looking all

around to see who was looking at me. No one was.

“Stop messing with that, will ya?” said Tim. “You’ll send

the boat down to Castleconnell and us here on the pier looking after it like a

right pair.”

I blushed. Tim was different from the boy I had known up in

Dublin. Since moving down the country he had learned things that were beyond my

reach. He knew how to fish and use a rowboat. He talked about girls and porter.

All the stories from my old school, from our old school, had seemed wrong in my

mouth when I told them that weekend. Like they belonged to someone else.

He kicked off from the pier and began to row. His back to

me, his arms worked us quickly towards the middle of Lough Derg. His neck was

dark brown, stained by the long June days on the lake or playing hurling in the

glen. I looked at my own arms, thin and pale. We were different animals now.

“Have a look in there,” he shouted over his shoulder. “In

the Dunnes Stores bag.”

I opened the bag and saw five or six pieces of twisted

scrap metal, each caked with a think black dirt. There was also a hand full of

bottle tops, some coloured stones, a rosary and an empty bottle of Powers Irish

Whiskey.

“What’s this?” I shouted up to him. “Is this the treasure?”

His capped moved. “What do you think of it?” he said. “Not

bad, ha?”

“It’s great,” I said. “Where’d you get it?”

My question brought an end to his rowing. He rested the

oars of the side of the boat and turned to face me.

“Come ere to me,” he motioned me closer with a turn of his

cap. “Can you keep a secret? They came from out there, from the island?”

“From the island?”

“From the Holy Island,” he said. “From the graves.”

I swallowed hard. He smiled, his teeth showing, and went

back to rowing.

“Now we’re having fun,” he shouted.

*

“I’m not doing it. I’m just not,” I said at last, my right

hand wrapped around the cast iron gate.

“Don’t be such a bloody baby,” Tim shouted. “This was you’re

idea. You wanted to see what my treasure hunts were like. Didn’t you?”

I nodded.

“We’ll come on and see then for Jesus sake.”

Tim was already standing on a grave, a small shovel in his

hand.

“I can’t,” I said, starting to cry. “I’m too scared.”

“Oh for Christ above sake,” he shouted. “You’re crying, you’re such a stupid bloody baby.” He started to pace back and forth across the grave, talking to himself more than to me. “All weekend, all you can talk about is your stupid stories from that stupid school. About those eejits back up in Dublin with the mammies looking after them. Is that what you want? Do you want your mammy? Is that it?”

I can’t exactly remember what happened next, but, by the

time we finished rolling around in the grave, I had a black eye and there was

blood coming from Tim’s nose. We rowed back to Killaloe in silence, each of us

taking one oar and working in unison. That night, after Tim’s mother had delivered

us a plate of ham and cheese sandwiches, we made up and played monopoly. They

next day, after mass, my father collected me from Tim’s house and brought me

back to Dublin. I shook Tim’s hand when I said goodbye and said I’d write, but

I knew I wouldn’t. We both knew.

We drove in silence across Tipperary, the June sun blaring

through the window. As we blurred past farm houses and forestry, I thought

about weekend, about Tim and how he was different now. My friend, my best

friend, was lost. I cradled my arms, raw with sunburn, and noticed two new

freckles had emerged on my skin. All I had left from the weekend.

No comments:

Post a Comment